>Originally posted September 02, 2007.

Ny Moral, along with bloggers Dan Eriksson, Si Vis Pacem Para Bellum, Becqon, Fas and Robsten, was encouraged by Oskorei to take some political tests. Read about Oskorei’s results here, and about some of his views here and here (Swedish only).

Oskorei… A very interesting character, indeed.

I took the tests, but first some disclaimers:

I tend to think too much sometimes, and that’s exactly what happens when I do these tests. They come off very stiff and are simply not made for my kind of mind. Some are very confusing. Some I cannot even answer properly because I don’t have enough knowledge, facts and/or understanding (for example, my knowledge about political economics is pretty slim…), or sometimes I may have chosen the “wrong” answer because I may have misunderstood the question. Also, these tests seem to be made for Americans.

And let’s face it, some questions are just plain stupid.

However, the tests may reveal some mindbending information about the moral and political stance that you may not know you had inside. They may help you understand why you think what you think, and since independent thinking is about trying to understand your situation everybody should give it a serious try.

Don’t take the results too serious though…

For your information:

I consider party politics to be extremely one dimensional, and thus not very creative or useful. The left and right bullshit told by those in power has lost its true meaning (and power) a long time ago. That way of defining political views is by no means applicable to the world and the societies we live in today.

Now let’s get on with the tests.

—

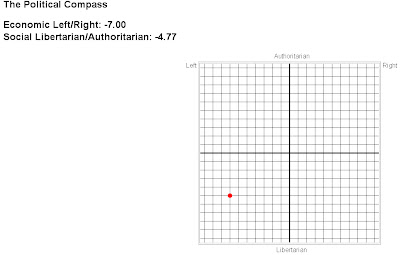

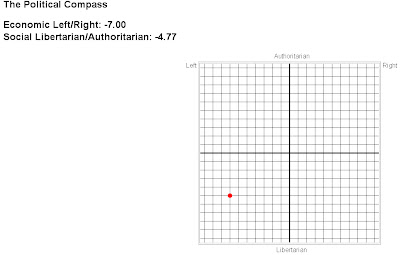

Political compass

This test is introduced with the following words:

The old one-dimensional categories of ‘right’ and ‘left’, established for the seating arrangement of the French National Assembly of 1789, are overly simplistic for today’s complex political landscape. For example, who are the ‘conservatives’ in today’s Russia? Are they the unreconstructed Stalinists, or the reformers who have adopted the right-wing views of conservatives like Margaret Thatcher ? On the standard left-right scale, how do you distinguish leftists like Stalin and Gandhi? It’s not sufficient to say that Stalin was simply more left than Gandhi. There are fundamental political differences between them that the old categories on their own can’t explain. Similarly, we generally describe social reactionaries as ‘right-wingers’, yet that leaves left-wing reactionaries like Robert Mugabe and Pol Pot off the hook.

My results:

Economic Left/Right: -7.00

Social Libertarian/Authoritarian: -4.77

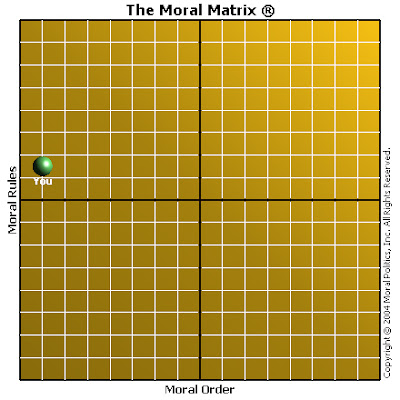

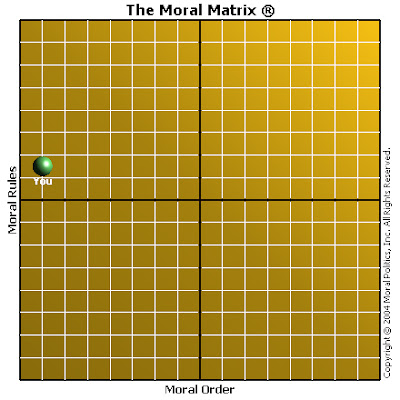

Moral politics

This test explains why you think what you think by mapping your personal moral system. Moral views are the major factors that influence political opinions. Every political stance can be explained by one’s moral position on the inner value of human beings and their role in society.

My results:

You scored -7 on the Moral Order axis and 1.5 on the Moral Rules axis.

The following items best match your score:

1. System: Socialism

2. Variation: Moral Socialism

3. Ideologies: Activism, Libertarian Socialism

4. US Parties: Green Party

5. Presidents: Jimmy Carter (85.18%)

6. 2004 Election Candidates: Ralph Nader (95.06%), John Kerry (76.51%), George W. Bush (39.69%)

PoliticsForum Quiz 2.0

My results:

Overall, the PoliticsForum quiz considers you a small-government, internationalist, protectionist, non-absolutist, kind of person.

These characteristics would put you in the overall category of social conservative protectionist. Your natural home at PoliticsForum would be the Conservatism area.

You scored 50 out of 100 on a scale of Individual vs Social. This means that politically you are neither more nor less likely to value the need for group actions and group benefit over individual enterprise and benefit.

You scored 55 out of 100 on a scale of Theist vs Materialist. This means that politically you are neither more nor less likely to believe that religion and spirituality are superstitions that should not inform political debate.

You scored 72 out of 100 on a scale of Big Government vs Small Government. This means that politically you are more likely to believe that government should keep out of legislating social policies, leaving such decisions to individuals.

You scored 61 out of 100 on a scale of Nationalist vs Internationalist. This means that politically you are more likely to favour international bodies over national ones.

You scored 36 out of 100 on a scale of Protectionist vs Free Trader. This means that politically you are less likely to favour free trade over protectionist policies.

You scored 65 out of 100 on a scale of Absolutist vs Non Absolutist. This means that politically you are less likely to believe that there is an absolute truth that may guide your ideological beliefs.

You scored 40 out of 100 on a scale of Controlled Market vs Liberal Market. This means that politically you are neither more nor less likely to believe that there is need for government regulation of industry.

You scored 50 out of 100 on a scale of Marxist vs Non-Marxist. This means that politically you are neither more nor less likely to follow the philosophies of Marx.

—

Phew! Interesting stuff. I’ll leave you without commenting any further and let you draw your own conclusions about my political stance and moral views, if you’re at all interested…