>

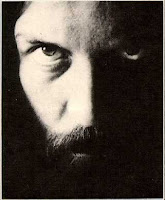

The Unabomb Taskforce of the FBI had – over 17 years – dealt with 3,600 volumes of information, 175 computer data bases, 82 million records, 12,000 event documents and 9,000 evidence photographs. And still they couldn’t catch the Unabomber, this one man living in a tiny cabin in Montana, terrorizing the country, killing innocent people.

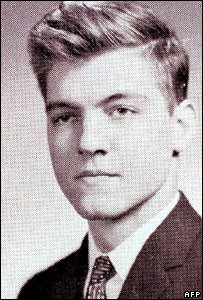

It was with the help of David Kaczynski, Ted’s younger brother, that they managed to solve the case.

Ted and David were very much alike. David admired his older brother for his ideals and conviction, and Ted enjoyed having an equal partner when it came to discussing philosophy, amongst many other subjects the two brothers shared similar interests in. Ultimately, faced with a moral dilemma, David turned his brother in. Theodore Kaczynski, who loved his brother, could not bear David’s betrayal and to this day deeply hates his whole family.

Yet the two were very dissimilar as well. Ted had no time for abstract philosophy or ethics, while David was more romantic, humble and sought discussion and was willing to compromise. Ted was unrelentless in believing he was right, he believed only in what was scientifically verifiable and rejected everything else as pure emotion. He thought of David’s abstract thinking as weak, and claimed David lacked energy and persistence, and he became furious when David summoned up the courage to argue back. Over time, though, his feelings of guilt about his unjust treatment of his little brother grew.

Ted began building his cabin in 1970. In 1985 David, obviously inspired by his brother, quit his job as a teacher, writer and bus driver, and also went into the wild. He bought five acres of land in the Christmas Mountains of West Texas and literally lived in a hole he had dug in the ground. Later on he purchased thirty acres nearby and – exactly like Ted – built his own cabin, living there until 1989.

In those days he was even more outspoken than Ted. He worried a great deal about the destruction of mankind, the destructive use of technology and the extreme materialism in our society. He often spoke about a need to revolt against it all. ”If he had known about my experiments”, Ted said later on, ”he would’ve regarded me as a hero”.

However, David’s conviction didn’t last. In 1989 he abandoned his desert home and moved to New York to marry an old girlfriend, a philosophy professor at Union College. This made Ted furious. He wrote a long letter to David about his ”betrayal of their shared resolve not to capitulate to the system”. David had ”committed the ultimate sin: ideological disloyalty”.

Ted believed all truths were like mathematics: either true or false. There was no room for compromise. Thus David – in Ted’s mind perfectly aware of the evils of industrial society – was living a lie when rejoining the middle class, and thereby proved his dishonesty. There was no forgiveness for such weakness and Ted turned to hate and total alienation.

By the early 1990s David began to worry about Ted’s extreme alienation. His wife said, half jokingly, ”You’ve got a weird brother, maybe he’s the Unabomber?”.